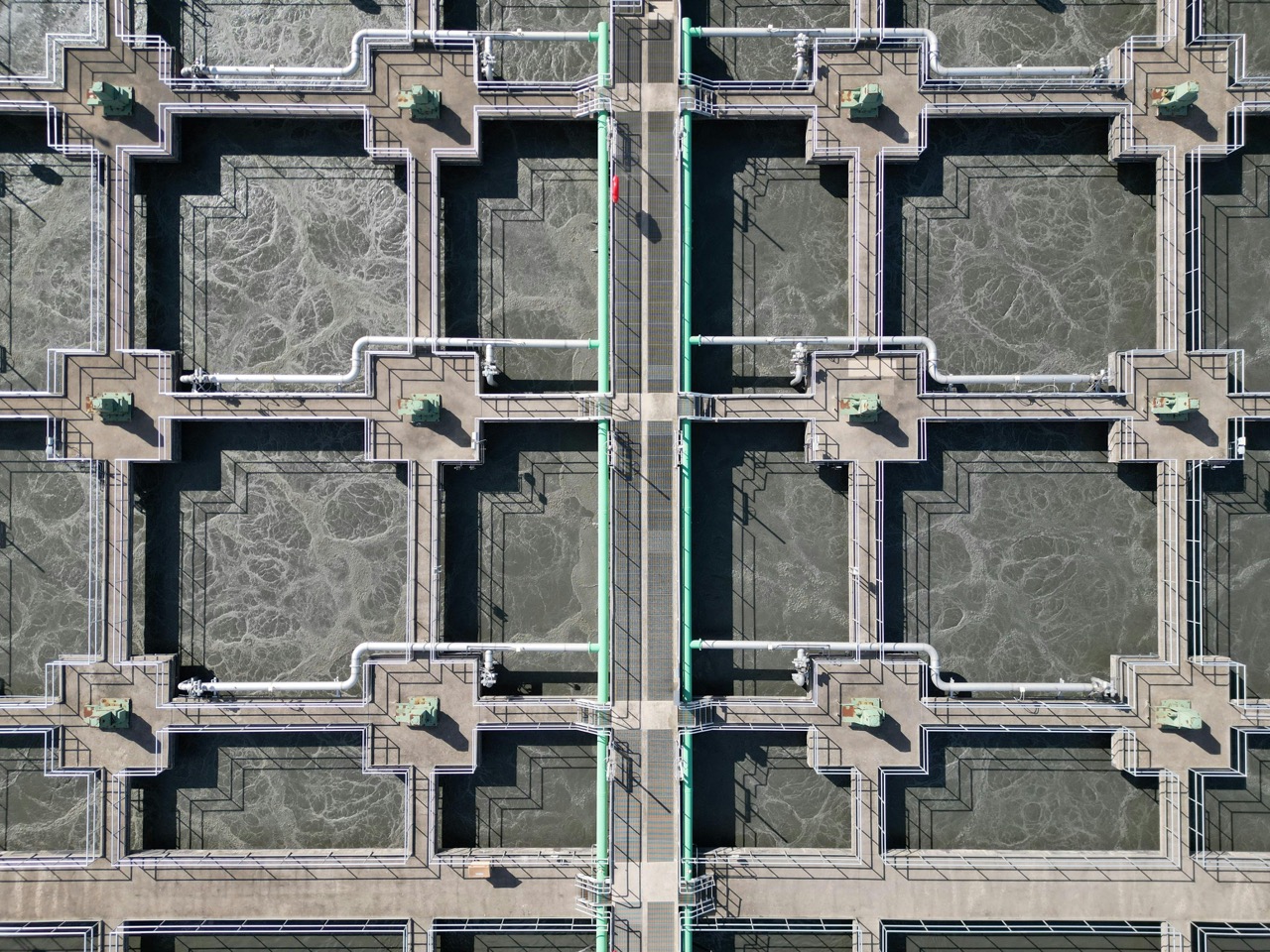

Operation of a wastewater treatment plant

Wastewater treatment plants use complex, interconnected technological processes to ensure that wastewater can be returned to the natural water cycle in order to protect the environment.

The purpose of a wastewater treatment plant is to treat wastewater arriving from households and industry via public sewers or tanker trucks to the legally prescribed limit values before it is discharged into the receiving environment (typically surface waters, or infiltration fields in the case of small-scale facilities). A forward-looking solution is the reuse of treated wastewater.

The required level of treatment is defined by the competent authority. Compliance with quality requirements depends on the applied treatment technologies. Since both the characteristics of incoming wastewater and the environmental sensitivity of the receiving water vary by location, each wastewater treatment plant operates with different parameters and must meet site-specific requirements.

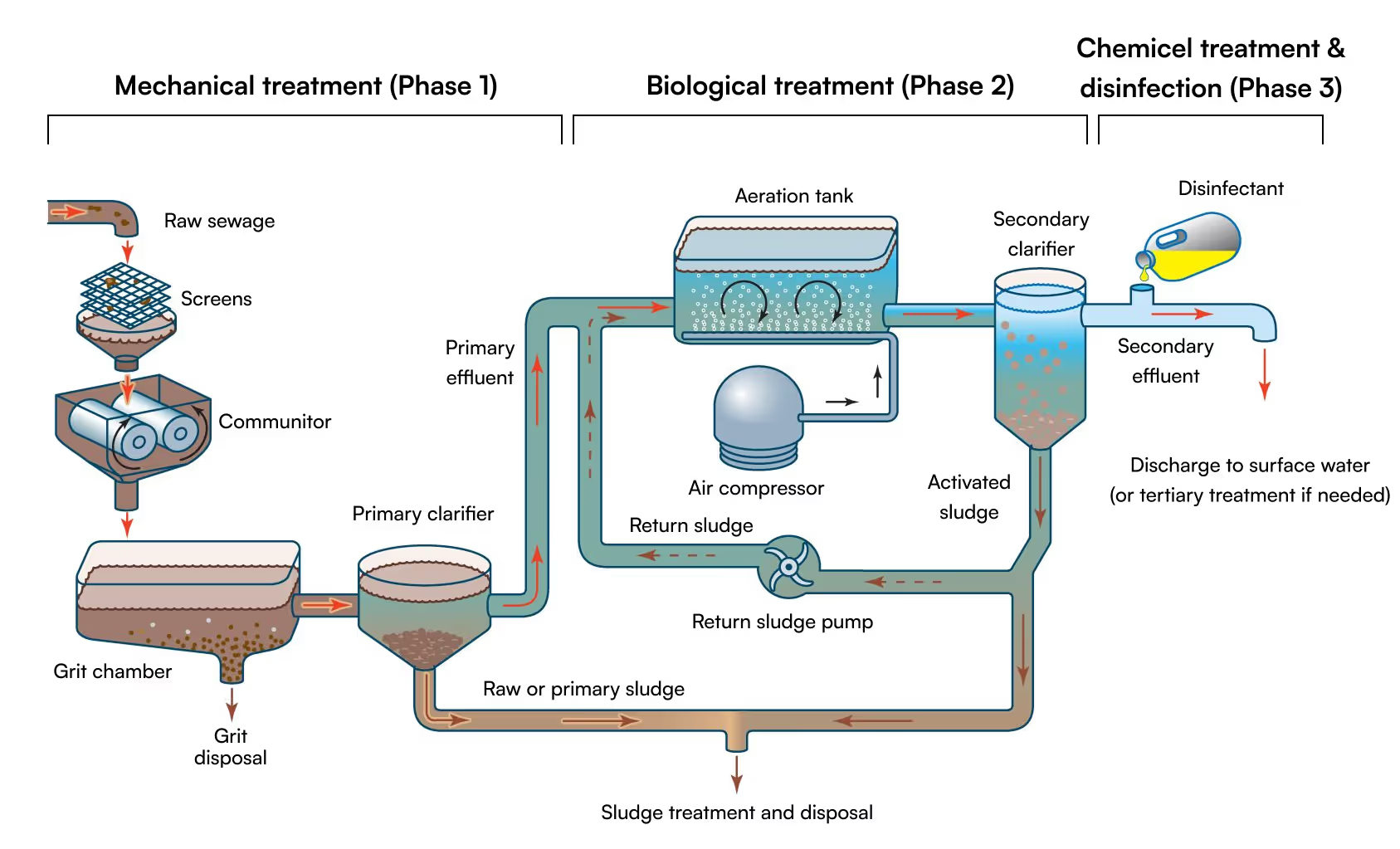

The operation of a conventional wastewater treatment plant consists of several sequential stages.

Mechanical treatment (Phase 1)

The first stage involves “coarse” separation. Larger solid contaminants arriving with raw wastewater are most effectively removed by mechanical means.

This mechanical treatment stage—often referred to as the preliminary treatment—uses screens of various mesh sizes and/or perforated drum screens similar to washing machine drums. Solid materials retained on the screens are known as screenings.

1. Coarse screen

- Screen spacing: approx. 20-40mm

- Removes: rags, plastic bags, branches, large debris

2. Fine screen

- Screen spacing: approx. 3–10mm (typically 5–6mm in modern plants)

- Removes: textile fragments, hygiene products, small plastics

3. Microscreen or drum screen

- Opening size: approx. 0.5–3mm

- Removes: hair, fibrous materials, fine suspended solids

4. Grit and grease removal

- Typically removes particles larger than 0.2 mm

- Removes: sand, gravel, glass fragments, fats, oils, and floating materials

In grit and grease chambers, scrapers collect settled solids from the bottom of the tank, while surface skimmers remove floating fats and foams.

Primary sedimentation

Depending on wastewater composition, some treatment plants include primary clarifiers where mainly organic solids are settled and removed from the wastewater by scraping mechanisms.

Utilization of by-products from Phase 1

Overall, approximately 30–40% of contaminants can be removed during the first treatment stage.

Screenings can theoretically be reused, but due to high separation and cleaning costs, they are typically disposed of in landfills or incineration plants. Materials removed in grit chambers—such as quartz sand, gravel, glass, and metal fragments—can be reused after cleaning, for example as road base material.

Primary sludge extracted during sedimentation is rich in organic matter and, after dewatering, is well suited for biogas production.

Biological treatment (Phase 2)

If mechanical treatment is the “anteroom” of the plant, biological treatment is its “living room.” In this phase, wastewater enters aerated tanks where microorganisms break down dissolved and fine suspended organic matter.

Main processes:

- Organic matter degradation (reduction of BOD and COD)

- Nitrification: ammonia → nitrate (aerobic conditions)

- Denitrification: nitrate → nitrogen gas (anoxic conditions)

The process relies on activated sludge, a complex community of bacteria and microorganisms.

What Are BOD and COD?

BOD (Biochemical Oxygen Demand) indicates the amount of dissolved oxygen required by microorganisms to degrade biodegradable organic matter in wastewater.

BOD₅ is measured over 5 days at 20 °C and expressed in mg O₂/l. Higher values indicate higher organic pollution. Raw municipal wastewater typically has a BOD₅ of 200–400 mg/l, while biologically treated effluent is usually below 25 mg/l.

COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand) indicates the amount of oxygen required to chemically oxidize all organic matter present in wastewater, including both biodegradable and non-biodegradable compounds.

COD is determined using a rapid laboratory test, typically applying a strong oxidizing agent (e.g. dichromate), and is expressed in mg O₂/l. Higher COD values indicate a higher total organic load. COD is a key complementary parameter to BOD, as it also accounts for persistent and poorly biodegradable pollutants.

How biological treatment works

Naturally occurring microorganisms consume dissolved organic and inorganic substances as nutrients. In conventional flow-through systems, nitrification and denitrification occur in separate tanks, spatially and temporally separated. In modern SBR (Sequencing Batch Reactor) systems, these processes occur sequentially within the same tank.

Biochemical processes

Nitrification (oxidation)

Ammonium (NH₄⁺) is converted into nitrite (NO₂⁻) by Nitrosomonas bacteria and further into nitrate (NO₃⁻) by Nitrobacter bacteria. Oxygen supply through intensive aeration is essential.

Denitrification (reduction)

Under oxygen-deficient (anoxic) conditions, nitrate is reduced to nitrogen gas (N₂), which escapes into the atmosphere. This step is critical to prevent eutrophication of receiving waters.

Secondary clarification (flow-through systems only)

Activated sludge flocs settle at the bottom of secondary clarifiers, allowing clarified water to flow onward. Part of the settled sludge is returned to the biological stage, while excess sludge is dewatered for further use or disposal. In SBR systems, sedimentation occurs in the same tank, separated in time.

Chemical treatment and disinfection (Phase 3)

Chemical treatment is not implemented at every wastewater treatment plant; however, due to the changing composition of municipal wastewater, the implementation of a third treatment stage has now become a regulatory requirement for new or refurbished plants. The removal of phosphorus—primarily originating from detergents entering the wastewater stream—is essential because, similarly to nitrates, it causes eutrophication (excessive nutrient loading) in receiving surface waters.

Phosphorus removal is achieved through chemical dosing, typically using iron or aluminum salts.

Disinfection is not a permanent part of wastewater treatment. When it is needed from time to time, it is also done with chemicals.

Sludge treatment

Sludge treatment is an integral part of wastewater treatment and significantly affects operating costs, environmental impact, and sustainability. The goal is to reduce sludge volume, stabilize organic matter, and prepare sludge for disposal or reuse. With appropriate technology, sludge becomes a secondary resource rather than waste.

Main steps

- Thickening (gravity, flotation, or mechanical)

- Stabilization (anaerobic digestion with biogas production or aerobic treatment)

- Dewatering (belt filter, centrifuge, or chamber filter press)

- Final disposal or utilization (agriculture, composting, energy recovery, landfill)

Micropollutant removal (Phase 4)

The revised EU Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive entering into force in 2027 explicitly addresses the removal of microplastics and pharmaceutical residues. Several advanced technologies are available:

- Chemical precipitation and sedimentation

- Advanced biological treatment

- Evaporation

- Ultrafiltration

- Advanced oxidation (photo-oxidation)

- Reverse osmosis

- Complex disinfection

The implementation of these technologies is a core competence of Water4All.

Discharge of Treated Wastewater

The discharge of treated wastewater is the final step in the wastewater treatment process, the purpose of which is to return the treated water to the natural water cycle without harming the environment. The discharge typically takes place into a surface water body (river, stream, lake), or in the case of smaller plants, into the soil through evaporation or reuse (e.g., for industrial or irrigation purposes).

The discharged water must comply with the limit values laid down in the legislation, in particular with regard to organic matter load (BOI₅, KOI), suspended solids, nutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus) and, where necessary, microbiological parameters. The limit values for each treatment plant are set and monitored by the competent authority according to the sensitivity of the receiving water body. Compliance with these values is essential to protect the oxygen balance, ecological status and water use objectives of living waters.